The New York Times published a story yesterday on the Aurora, Colorado shootings entitled, “Before Gunfire, Hints of ‘Bad News’.” We’re a long way from fully understanding the significance of the shootings, but the Times’ piece is a reasonable consolidation of facts, so I’ll use it here to make the point that discharging a duty to prevent violence rests heavily on the processing of information to understand the nature of a potential threat.

The Times on the Aurora shootings

The Times follows the classic line of inquiry that follows incidents of violence. Who knew what about suspected shooter James Holmes? When? And why didn’t they act?

The Times goes over facts raised very soon after the shootings about concerns held by Holmes’ psychiatrist, also the director of student mental health services at the University of Colorado Denver. Holmes attended UC Denver until he voluntarily withdrew from study about a month before the shooting. The Times also adds new facts garnered from interviews with people who had recent contact with Holmes. Most notably, in May, Holmes told another student that he had purchased a Glock semiautomatic pistol. Holmes also had some puzzling interactions with a different student about his mental condition, warning her to stay away “because I’m bad news.”

We should not be surprised by these findings. As the forensic psychiatrist quoted by the Times notes, “almost without exception, [mass killers’] crimes represent the endpoint of a long and troubled highway that in hindsight was dotted with signs missed or misinterpreted.”

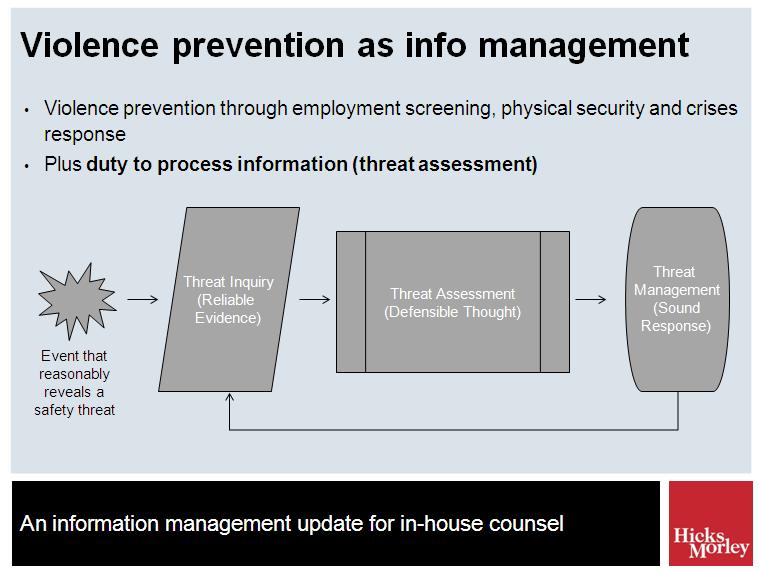

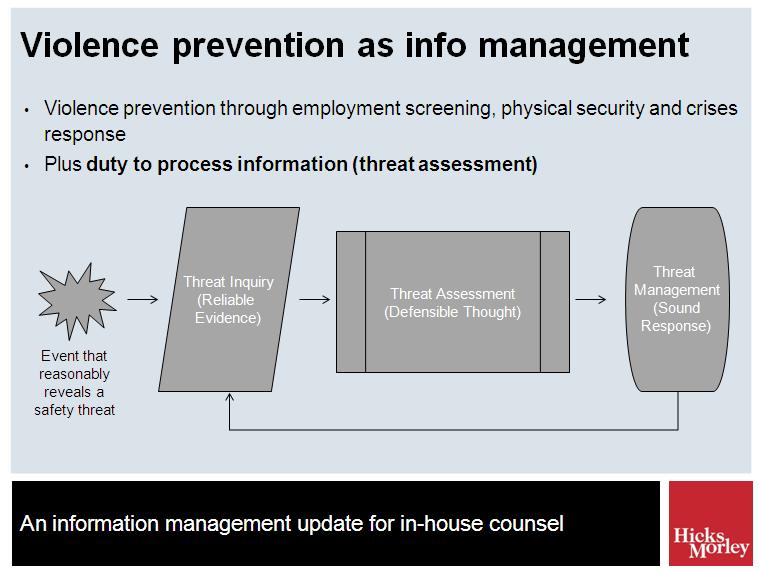

This widely-accepted view is why violence prevention rests so heavily on processing information or, more specifically, on “threat assessment.” Whether a duty to prevent violence is based on workplace health and safety legislation, occupiers liability legislation or common law duties, implementing reasonable employment screening, reasonable physical security controls and a reasonable emergency response plan is not enough. Implementing a reasonable threat assessment system is an important part of violence prevention, and is necessary to manage the risk of violence that is perpetrated by individuals who are “knowable” to an organization (e.g., customers, patients, students, current and former employees and domestic partners of current employees).

What is threat assessment?

Threat assessment is a structured process of identifying, assessing and managing the threat that certain persons may pose to others. It is depicted in this slide I have prepared for an upcoming presentation (details and registration here):

The element of the process that is highlighted by the Times’ article is on the very left of the slide. A duty to employ reasonable threat assessment procedures requires organizations to build and maintain a system for picking up on and evaluating available or knowable information that might indicate a risk of violence. The duty to “know what is reasonable to know” supports the reporting of threats and mere behaviors of concern, supports the imposition of reporting duties on employees and supports the use of communication and training to encourage others (such as students and customers) to report.

Yes, threat assessment systems invite a kind of surveillance. However:

- their use is supported by a very strong and consistent body of authority;

- they have become a regularly utilized part of the health and safety programs at all Canadian universities and colleges (who are particularly open to the risk of violence from “knowable” individuals); and

- they are a key part of a workplace violence prevention and intervention standard approved by the American National Standard Institute in 2011.

Though threat assessment has an impact on personal privacy, it is a justifiable impact. The British Columbia and Ontario privacy commissioners have published a guideline on violence prevention that declares “life trumps privacy.” Though the guideline focuses on the disclosure of personal information post-assessment and as part of threat management, the principle it supports applies equally to justify the collection of personal information for threat assessment purposes. In fact, one may question whether a disclosure of personal information for threat management purposes can be made responsibility if it is not based on sound fact-based analysis that can only be achieved with through collection of personal information that helps an organization understand the threat.

Hard questions about the Aurora shootings

Though the Times has compiled some facts that, in hindsight, paint a “disturbing portrait of a young man struggling with a severe mental illness who more than once hinted to others that he was losing his footing,” this does not establish that Holmes’ university failed in assessing the threat that he posed. In fact, at this early stage the Aurora shootings raise some very difficult questions about UC Colorado’s responsibility.

First, what does the reasonable educational institution do to encourage student reports? One student received a warning from Holmes and another knew he had a firearm. UC Denver’s website indicates that faculty and staff have a duty to report threatening and concerning behaviors, but it does not appear that the university imposed such a duty on students. Is this approach reasonable? Would such a duty be meaningful or enforceable in any practical way? What did the university do to encourage or facilitate reporting by students? Was that reasonable?

Second, when should health care providers employed by an educational institution report behaviors for threat assessment? Mental health professionals hear about all kinds of concerning behaviors in the course of providing health care. They are duty-bound to keep such information confidential subject to, under our law in Ontario, a belief that disclosure of information is necessary to eliminate or reduce a significant risk of serious bodily harm. Such disclosures will ordinarily invite an immediate (emergency) response by law enforcement and not threat assessment, so the media’s early focus on what Holmes’ psychiatrist knew and disclosed for threat assessment purposes is puzzling.

Third, what duty does an educational institution have to the public at large? UC Denver is a public institution with an educational mandate. It has no public safety mandate and no relationship with the shooting victims. Does its mere engagement in assessing the threat posed by Holmes to its community justify the imposition of a duty of care to others? This is questionable.

For more information on threat assessment

Here are the resources I’ve used in preparing this article and in preparing for my upcoming presentation.

I’d also encourage you to follow David Hyde, who regularly shares insightful information on threat assessment. For David’s recent post on the role of threat assessment in a workplace violence program, click here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.